A while back Vickie Obermaier, a descendant of Clarkson’s Kudrna clan, sent me this interesting portrait of a haymaking crew taking a break from their labors. Mugging for the camera, they stand stock-still in their poses (only the blurred horses’ heads betray the long shutter speeds of the old camera). Two of the farmers are holding stoneware crocks of… lemonade? All sorts of little details can be made out from this old photo – steel-wheeled hayracks, fly nets on the draft horse harnesses, some sort of row crop in the background.

Seven wagons bulging with hay, it is a picture of agricultural prosperity – the Promise of the New World. This was a major reason many came to America in the first place – work hard and get rich. There is little doubt that the men were enjoying their brief rest before pushing on to the painstaking (and dusty) task of constructing haystacks. And there is no doubt that they are unaware that the prosperity to which they have been accustomed was about to come to a sudden end. These happy farmers were on the verge of a two-decade long period of hard times.

The 20 years between 1899 and 1919, when many of our immigrant ancestors were getting established in Nebraska, are generally considered to be a time of prosperity for Midwestern farmers. The protracted drought and nationwide financial panic that began in 1893 was over by the end of the decade, and both crop yields and crop prices began to climb. Although the wheat yield was no greater in Nebraska than it had been in Europe (both ranged from 12-22 bushels per acre at that time), there was SO MUCH LAND. The availability of large areas of fertile land (e.g., via the Homestead Act), improvements in agricultural equipment, the introduction of hard winter wheat, and the extension of the railroads (which helped our farmers reach world markets) all pushed farming into high gear. The price of corn tripled and wheat more than doubled between 1910 and 1918. With huge domestic and overseas markets, the wealth of many Clarkson-area farmers was limited only by how much wheat they could thresh and how much corn they could pick by hand.

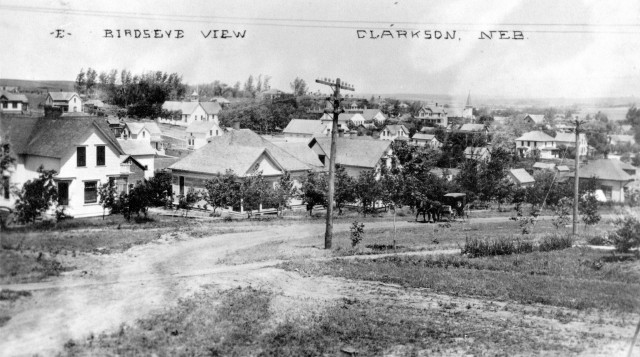

The Village of Clarkson prospered along with its farmers. By 1898 a large grain mill and elevator had been built along the railroad tracks. A 64,000 gallon water tower was constructed in 1904 and a rudimentary telephone system in 1905. Twenty five new homes were built in Clarkson in 1905 alone.

By 1911, Clarkson had grown into a tidy little town nestled in the hills of Eastern Nebraska, with lots of well-kept wood frame houses and brick commercial buildings, and plans for the new brick high school (dedicated in 1913).

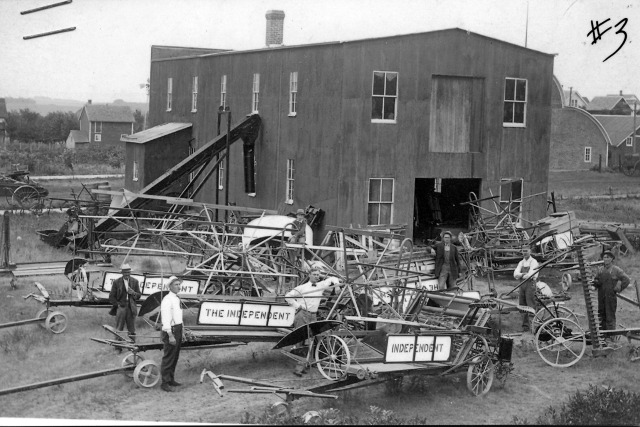

The booming farm economy supported the manufacture and sale of agricultural equipment.

By 1918, the date of the picture at the beginning of this story, the Farmers Union Co-Op Supply Co. had begun construction of a grain elevator along the railroad tracks to further facilitate the shipment of area farmers’ wheat to the World.

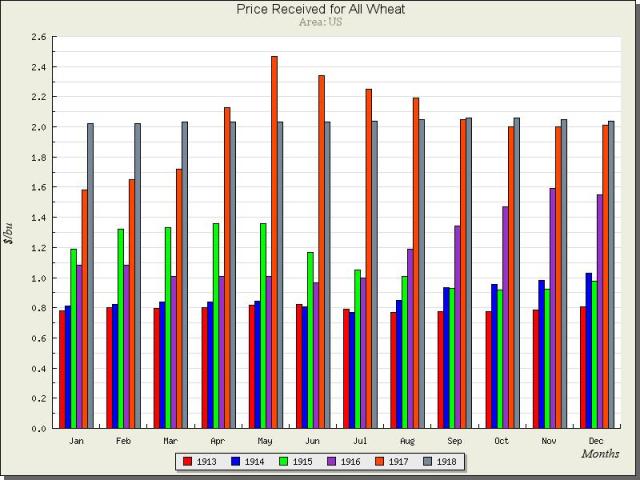

And in 1918, the World was hungry. The First World War had devastated food production in Europe, and American farmers stepped in to fill the empty stomachs. Before 1914, Great Britain, France, Belgium and Italy (our allies) had depended heavily on other European countries, as well as Australia, Argentina, Canada, and the U.S. for much of their food supplies. When many of these trade channels were disrupted in 1914, European demand for American farm products soon exceeded the supply, and prices skyrocketed. The price of corn paid to Nebraskans increased from $0.99/100 lbs in 1913 to $2.58/100 lbs in 1919. The price of livestock and livestock products jumped almost as fast. In the five years before 1914, American farmers were paid an average of 90 cents a bushel for their wheat. As Allied purchasing agents began bidding against one another and speculators jumped in to take advantage of the situation, the average price rose to more than $2 a bushel in 1918. The net income of U.S. farmers, after paying for supplies, rent, taxes, and interest on their loans and mortgages, increased 120 percent from 1914 to 1919 (the net income of the non-farming population increased 75 percent during those years).

With the end of the First World War in November 1918, the need to feed large armies decreased, and European farmers were able to return to their shellhole-ridden farms to feed their own people. By 1920, European agriculture was returning to normal, pre-war trade had been re-established, and European nations had borrowed so much money from the U.S. that they no longer had money to buy food from U.S. farmers. This led to a collapse in demand and a collapse in farm prices.

Corn dropped from a 1918 high of $2.58/100 lbs to $0.79/100 lbs in 1922. Expressed another way, corn brought 52 cents a bushel in 1921, a 60 percent drop in two years. The price of wheat in 1923 was less than half of the 1919 peak.

Imagine the dismay of area farmers who had borrowed large sums of money to buy more land during the war years. Almost overnight, they were squeezed by receiving low prices for what they produced and paying heavy fixed charges – taxes and interest on loans and mortgages.

Although prices for farm products recovered somewhat after 1923, farmers in general did not share in the seeming prosperity of the rest of the Nation during the Roaring Twenties. The graph below suggests that after a brief uptick in wheat prices in 1925, the value of farm crops dropped relentlessly until 1932. Corn dropped from $1.58/100 lbs. to $0.44/100lbs in those same years.

And we all know what happened in the 1930s – in 1931, Nebraska entered a 10-year period of drought that was one of the worst on record. Low prices coupled with low production. If the left fist doesn’t get you, then the right one will.

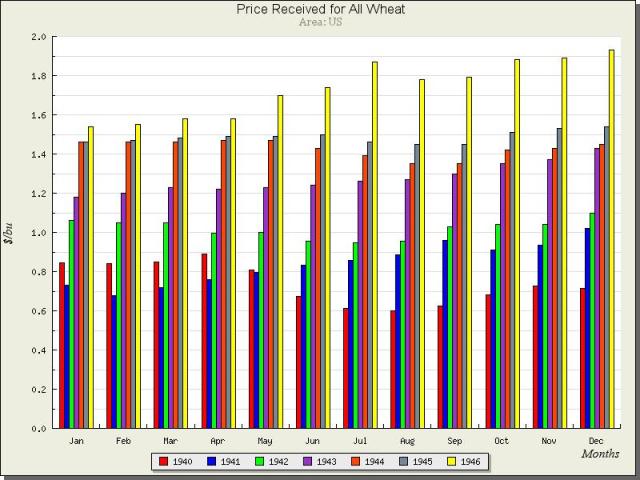

And once again, a World War increased the demand for U.S. farm products, and beginning in 1940 prices rebounded. The price of wheat rose from about $0.70/bushel in 1940 to over $1.90/bushel by the end of 1946, as American grain helped feed starving multitudes and became a significant component of foreign aid after World War II.

Clarkson-area farmers finally saw profitable years return in the 1940s, the 1950s (despite another drought between 1952 and 1957), and many years thereafter.

My point is that the Great Depression, which was such a terrible, defining experience for the entire United States, lasted 10 years longer for Nebraska farmers than it did for many others. Those who were well-established on their farms, relatively free of debt, and good at tightening their belts were able to make it through the bad times between 1921 and 1941. Late arrivers, those who expanded their farms at inflated, wartime prices, and those with large debts and mortgages, struggled and sometimes lost everything. This was a greater problem in the Rocky Mountain West and the Dust Bowl areas of Oklahoma, Texas, Colorado, and Kansas than in the eastern Great Plains; settlement of eastern Nebraska was essentially complete before World War I, and farmers had learned to be cautious about the climate. But the conjunction of low prices and low yields certainly caused hardships in Our Town. Banks and businesses folded. Farmers who engaged in back-breaking labor every day of the year counted their annual profits in tens or hundreds of dollars (or none at all). Most were able to hang on through two decades of lean years.

I suppose that’s why the people of Clarkson are so resilient and unshakable.

[Disclaimer: The more I look at this picture at the top of this post, the more I think that the men may be standing on shocks of wheat, heading for a thresher, rather than on hay on its way to a haystack or hay barn. I consulted the authorities: Marvin Podany suggested that the men may have been standing on bundles of oats, because the picture shows too many racks of grain to be taken to a threshing machine at one time (apparently bundles of oats were stacked and treated differently from wheat). Kerry Bahns thinks it looks like wheat stubble. Perhaps some member of the Future Farmers of America, Class of 1920 or so, can settle the question.]

References

Anonymous. Shall I Take Up Farming? What Are The Lessons From The Last War? Constructing a Postwar World – The G.I. Roundtable Series in Context. www.historians.org/projects/Giroundtable/Farming/Farming6/htm

Cerman, M. 2008. Rural Economy and Society. Chapter 3 in A Companion to Eighteenth-Century Europe. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Gould, B.W. 2013. Understanding Dairy Markets. Online database. http://future.aae.wisc.edu/

Hayes, M., C. Knutson, and Q.S. Hu. 2005. Multiple-Year Droughts in Nebraska. NebGuide G1551. University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension, Lincoln, Nebraska.

Jones, L.A. and D. Durand. 1954. Great Plains and Mountain States. Chapter 2 in Mortgage Lending Experience in Agriculture. Princeton University Press.

Montgomery, G. 1953. Wheat price policy in the United States. http://econpapers.repec.org/article/agsiuppap/17204.htm

Wow! What an interesting report…Great pictures! ele

I have to agree, looking at the stubble, looks like wheat…this year in parts of Kansas, 100 bushels of wheat were harvested…eat your heart out 1919….

I’m sorry–I’ve been moving and out of touch!! What great articles!! the one thing that impresses me about the Bohemian farmers who came to Nebraska, eventually, is how brave they were!! They left at least fairly decent lives and, at least in the case of my great-grandfather Shonka, arrived on the prairie to find NOTHING on the piece of prairie that he claimed—no barn, no house, nothing!!!

Plan to include these stories in the family history that I am working on — Endlessly!! Roberta Shonka Ortwein.

Thanks, Roberta. Putting together family histories can really eat up your time, but they are so important. I’m fortunate that my brother and his wife took care of that for our family.

Are you descended from the Matej and Marie Shonka family of the Abie/Schuyler area?

These are neat pics and info! Thanks for sharing! I would like to know more about one of the pictures above a few pictures up from the last. If you would know anyone I could call that would be great! Appreciate it!

Jack – I’ll be happy to figure out where the photo came from. Send me an e-mail ( gfpmc49@tds.net ) that describes the photo and I’ll get back to you.

Glenn

Jack –

The photo you asked about was a windrower (swather) that was jointly owned by my Dad and his brother. The man on the tractor is my older brother, Larry. This is what Larry remembers about it:

This was a weird machine, almost a Rube Goldberg design. I haven’t seen one before or after, don’t know the brand or where it came from.

Apparently some literature or a salesman came and talked to our uncle about trying it out. Since we needed a better windrower (ours was made from an old binder with a 5′ cut) we decided to go ahead with it. I was somewhat involved in putting it together.

It worked ok, was strange to drive, took a lot of different coordination. The lever I’m holding is for steering and there were cable extensions for the clutch/brake and other extensions for the gearshift and throttle so for some you had to reach behind your back. To move it the seat turned around and drove it somewhat normally, The problem in moving it was that it was quite heavy and the front end kept trying to come up.

I don’t know what happened to it, the last I knew it was sitting in the trees at our uncle’s farm and I don’t remember it selling at his farm sale….

I got curious about it and did a quick Google search. The only thing I turned up was a 1948 thesis from Iowa State College that describes the design and development of a rear-mounted grain windrower. https://dr.lib.iastate.edu/entities/publication/cb141187-1506-43c2-93a3-8ba1da799a98

There is a photo of the prototype on page 60 of the Iowa State thesis. It looks very much like the windrower that my brother was operating.