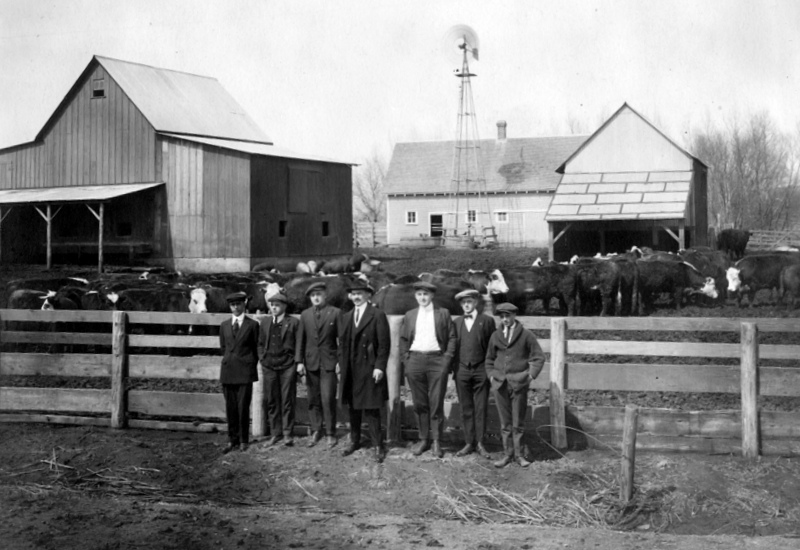

Earlier this year we visited the National Czech & Slovak Museum in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. One of their temporary exhibits was a collection of fascinating black and white photographs taken by Igor Grossman, a pharmacist who lived in a rural Slovak village in the 1950s and 1960s. To quote from the museum’s description of the exhibit, Grossman “… realized that the life ways and customs he experienced were part of an old world that was rapidly being replaced with a modern, communist one. He took up his camera to document those customs before they were gone. Grossman’s photographs capture the landscapes, people, and traditions of Slovak mountain villages, portraying the moment of transition between the old world and the new. As written in the introduction to Grossman’s book, Images Gone With Time, Grossman’s photographs are the land of our memories of home. They are a record of our existence, a guarantee of our survival.”

There were many priceless, timeless photographs in the exhibit, but the one that stopped me in my tracks was a picture of a grinning man hoisting a shot glass (kalíšek) of some liquid (slivovice?). He was apparently toasting the successful dispatching of a hog, and would soon begin the considerable effort of butchering it.

Although we all go to grocery stores or butcher shops to get our pork chops these days, there are a few of us who can still remember the time when farmers butchered their own hogs, using their own or borrowed tools. In the late fall or early winter, when temperatures were suitably cool and the hogs had gotten suitably fat, a candidate for slaughter was selected from the hog pen. The animal would be killed, cleaned, and butchered in a laborious, day-long process. Sometimes this would be done by a single family, but because it was a relatively specialized, once-a-year activity, often several neighbors or families might come together in a group effort, sharing the tools and the physical labor.

There are a lot of body parts to a pig, and the Czechs, being a frugal race, have managed to find a use for most of them. Many years ago, my father-in-law and I were discussing the details of hog butchering and all the consumer products that could be made from them, and he capped the conversation with the remark – “The only part of a pig that we threw away was the squeal.”

That statement is worth examining, because it is nearly true. I can remember only the last time that my parents butchered a hog at our farm, when I was still a small child. After that, they let the town butcher take care of business. So the details are sketchy in my mind (my memories have been verified by my older brothers). But it went something like this (those of you who are squeamish may want to skip this part, and, in fact, the rest of the story):

Step 1. Dad chased us away and we waited in the house or behind a nearby shed while he killed the hog, probably with a hammer blow to the head.

Step 2. A chain was attached to the hog, perhaps through the back legs, and by means of a pulley the heavy carcass was lifted upside down over a large wooden trough (see the photograph above).

Step 3. A vein in the hog’s neck was opened with a knife and the blood was drained into a stainless steel or porcelain dish pan for later use.

Step 4. The hog was lowered into the trough and immersed in scalding hot water. After a few moments, Dad began to scrape the hog’s skin in order to remove all the hair from the carcass. Brother Larry says that there was a specialized tool to do the scraping/hair removal; it was a wooden handle with a circular metal disk on both ends, one maybe 4” in diameter on one end and 2” on the other.

Step 5. The hog was elevated again, rinsed off, and a long cut was made in the abdomen to remove the internal organs. This is the point at which the dogs and cats became interested.

Step 6. By means of very sharp knives and bone saws, the hog was dismembered into its constituent parts and sent to the house, piece by piece, for further processing and packaging.

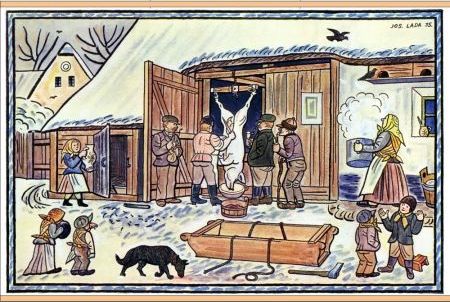

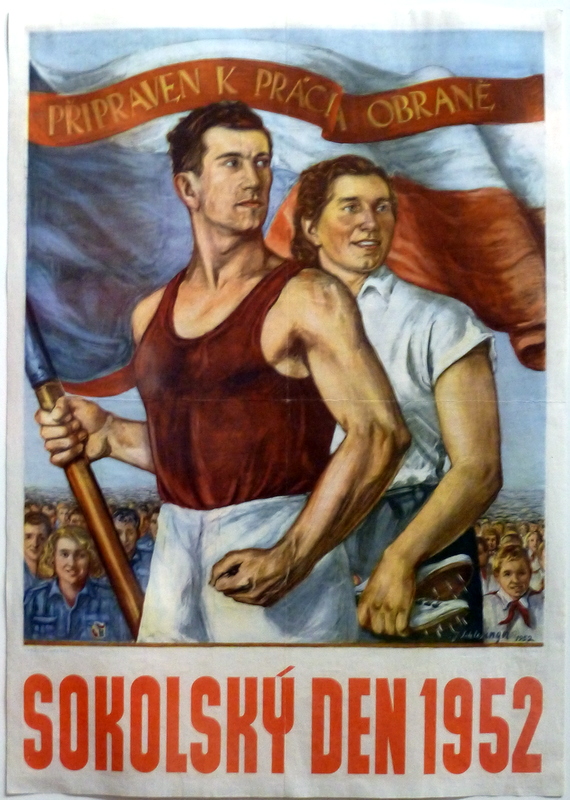

The painting below by the renowned Czech artist Josef Lada illustrates much of the process. In the Czech Republic, pig slaughtering was a special event, accompanied in some cases by ceremonies, gift-giving, and other festivities.

Truth be told, I didn’t witness any of Steps 1-5 except from a safe distance, but I think the sequence of the general events is correct. Once the pork was brought inside the house, there was more activity with sharp knives, saws, and hot liquids. The larger pieces of meat were turned into pork roasts, pork chops, etc. and were packaged in brown, waxed, butcher paper and frozen. The smaller pieces of meat (scraps) were ground up and cooked along with some spices and pieces of cartilage from the ears and made into the quintessential Czech sausage – jitrnice.

I’m sure I don’t have to tell you how to make jitrnice – you all have your favorite recipe. But in the Old Country at least, this sausage is a delectable blend of cooked meat from the head, wattles, and hips, boiled lung, spleen, and stomach, raw liver, cooked liver, white bread, onions, and spices (black pepper, allspice, garlic, ginger, marjoram, and salt). If you want to make some yourself, you can find the correct proportions here: http://czechthatout.wordpress.com/2011/10/10/a-half-of-a-pig/

It begins with cooking the hog’s head…

If you can’t be troubled to retrieve all the body parts called for in the Old Country recipe above, the book Favorite Czech Recipes For Today’s Kitchens (blue-covered edition) compiled by the Clarkson Woman’s Club has a good recipe that limits the “variety meats” to pork tongue, heart, liver, hocks, and head.

After the meat and spice mixture was put together, it was stuffed into casings (the polite word for thoroughly washed small intestines). I couldn’t find a picture that looked exactly like the sausage stuffer that we used, but it looked something like this:

The sausage mixture was put into the cannister, the gear mechanism/plunger was affixed to the top, and great lengths of wet hog casings were slid over the tube at the bottom of the cannister (white plastic in this picture, thin aluminum in ours). The operator slowly cranked the handle which moved the plunger downwards and squeezed the sausage mixture out of the tube and into the casings. Voila!

Next comes sausage made from the reserved pig blood – jelita.

Actually, this was one of the first items of business when butchering a hog, because you had to keep stirring the warm blood to keep it from clotting. Then the blood was mixed with a variety of ingredients similar to those for jitrnice and stuffed into casings. Every family/butcher had their own recipe, but most of them included barley. A good mixture was about 1 pound of barley for each quart of blood. Again, my brother Larry confirms that the pig’s blood was brought into the house ASAP but our parents never stuffed jelita into casings. They would put it into a pan, like a big cake pan, add barley and spices, then kept stirring it. It ended up looking like a very dark chocolate cake that our dad would cut and eat like a brownie. (As odd as this may sound, blood sausages and blood puddings are common all over the world. Take a look at the black sausages at breakfast buffets in the British Isles, for example).

Moving down the line, we come to one of my personal favorites – sulc. Sulc (aka sulz, head cheese, or souse) is a gelatinous treat made from pigs feet, and often pig snouts and skin as well. The feet are cooked with salt, pepper, bay leaf, carrots and onion. The bones are removed, a bit of vinegar is added, and, when refrigerated, the mixture congeals into a meat gelatin.

Others prefer to use the feet to make marinované vepřově nožičky (pickled pigs feet).

Hungry yet? At some point, late in the proceedings, the large chunks of lard that had been cut away from the meat were put into a huge pot and slowly melted down (rendered) on the stove. The skin and connective tissue that remained in the molten fat were fished out with a strainer, drained, run through the sausage stuffer to press more lard out, crumbled up, and eaten warm with fresh bread – škvarky. Škvarky (similar to what is known in other cultures as cracklings, pork rinds, or chicharrones) are crispy, greasy, and delicious – the ultimate guilty pleasure food. For the uninitiated, they MUST be eaten warm in order to prevent the cold lard from sticking to the roof of your mouth. Some insist that the bread must be rye bread, with a sprinkling of caraway seeds, but I am not so particular. I only remember eating cracklings fresh, late in the day of butchering. The excess pressed-out cracklings were thrown into the trees for the dogs and cats to eat.

The molten hog lard was then poured into jars for use in cooking (how can a pie or any flavorful bread or pastry be made without lard?). Usually there was more lard than a family could consume, so the rest was used to make homemade soap. The recipe from homemade soap is simplicity itself – into the hot, liquid lard an appropriate quantity of lye (sodium hydroxide) crystals was stirred. The lye saponified the fat, turning it into hot, liquid soap. Then Mom or Dad would pour the liquid soap into a cardboard box, to a depth of 3 inches or so. The soap would cool and solidify into a solid white sheet that could easily be cut into soap bars with a knife. This was harsh, strong stuff – in our house, it was used in conjunction with a washboard to get the most stubborn dirt from work clothes – overalls and socks. Again, we were kept a safe distance away during the rendering and soap-making so that we would not be burned by the hot, caustic liquid.

Let’s see – have we accounted for all the body parts? Liver, ears, feet, snout, spleen, small intestines… Oh yes, the brain. In those days, as now, brains were scrambled. With eggs and, for the gourmet, with mushrooms. Don’t ask me how it tastes. But the Clarkson Woman’s Club Favorite Czech Recipes book has an easy Scrambled Eggs with Brains recipe for the busy modern housewife. In fact, the cookbook has recipes for all the food items mentioned in this story.

So let us pay homage to the humble swine. Maligned in the Bible (read the story of the Prodigal Son), this versatile species turns garbage and corn husks into delicious protein with a multitude of uses. Ask your friends – what other animal provides us with škvarky, jitrnice, jelita, and sulc? With fat to make both delicate pastries and soap for scrubbing the dirtiest overalls? A noble animal that gives us not only sausage meat, but also the casing to put it in.